- ARPDAUPosted 12 years ago

- What’s an impressive conversion rate? And other stats updatesPosted 12 years ago

- Your quick guide to metricsPosted 12 years ago

Taking your F2P game and making it paid–the story of Jagged Alliance Online

This is a guest post from Jan Wagner, Managing Director of Cliffhanger Productions. He recently took his F2P game, Jagged Alliance Online, back to being a paid game on Steam and I asked him why. This was the answer.

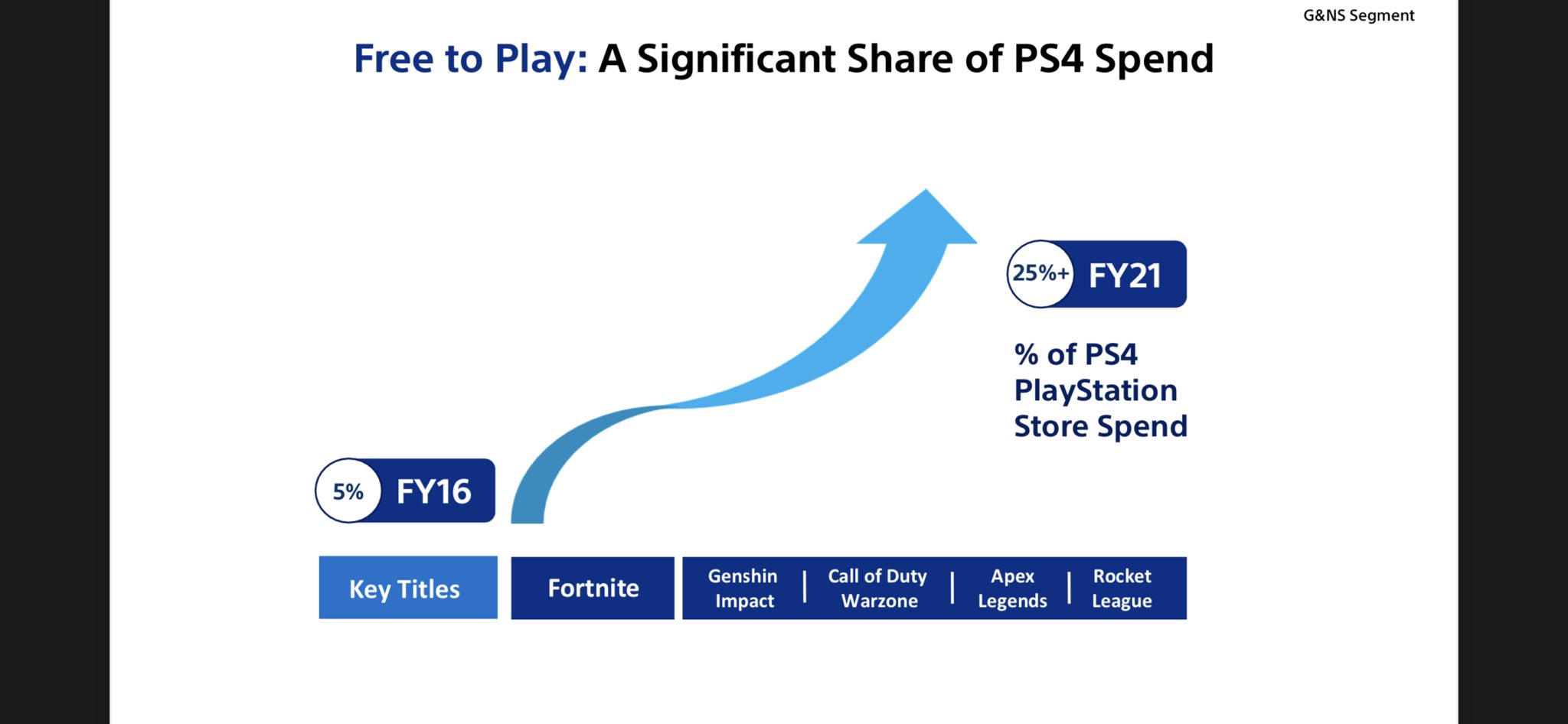

Recently the free to play scene has realized that the endless rapid growth they are used to is limited. Even though f2p dominates online and mobile platforms the vast majority of titles fail as the very top tiers fight for customers by pushing acquisition to ever higher prices. With the increased amount of online games and the decreased retention times, players jump from title to title and the market is getting difficult even for the big players. But the received wisdom is that any game with a multiplayer component has to go free to play to sustain itself and get enough customer to survive. Cliffhanger Productions however has gone the opposite way – we have brought all of our games back from f2p to pay to play. Let me explain.

At Cliffhanger, we have been doing online RPG/tactical games for half a decade on PC as well as cross platform on mobile and as an independent developer have looked for a niche to establish ourselves in. This niche for us is turn-based games for a more mature audience in the 30-45 age bracket and a core sensibility ideally in a genre and with a license that resonates with them. Our first title was a work for hire project named Jagged Alliance Online (back then as a browser game), subsequently we released our cross-platform game AErena (which won us a number of awards and got featured by Apple and Google) and PC Online title Shadowrun Online (now Shadowrun Chronicles), all of which were meant to be free to play games initially. For Shadowrun we didn’t even attempt to make a free to play version anymore and the other two we have brought back to pay to play (apart from AErena on mobile, that still exists in both variants).

All of these games have in common that, while they are accessible, they are clearly core games and require a certain amount focus to play and can get very deep. As a consequence they had a relatively low week 1 retention (for Jagged Alliance Online it was around 35% for day one but below 15% for week 1 and for AErena it was around the same on PC and about 25% day one on mobile with less than 10% for the first week). On the other hand, we had a monthly ARPPU of around 50€ to 60€ on JAO and 3-5% of people playing for months and sometimes years, once they got past the initial phase.

Conventional wisdom suggests, that we could sustain ourselves if we managed to monetize the heck out of the small player base and perhaps improve week one retention and so we tried to do this for some time. But here is the first catch: As an indie studio we have limited means to increase our player base through acquisition (which is why we went for branded games early on) and we cannot afford to fiddle with retention improvements endlessly nor in fact can we afford to just drop a title and do the next. After iterating and improving our early retention another thing became clear: The established industry formula we were basing our forecasts on, which is assuming that a given percentage of players in every batch of new players will be “the right ones” and you just need to optimize your acquisition by what to this day remains trial and error (no matter how fancy the names for it get) simply did not hold true for us. The number of player we retained long term did not much change even when we brought our day one retention to close to 50%. At the end of the months the same amount of players stayed as before.

That could be entirely our fault, could speak to the quality of the game or to the type of game we have made and the people attracted by it, but that is not the topic of this article. We were left with a problem: We had two titles (and another one in the pipeline), that weren’t performing as expected and we had run out of time and money to try and change that or throw advertisement at them. Our strategy had been to get initial traction by delivering what (at the time) was superior quality and deeper game play compared to other games in that space. And while we managed to succeed in attracting over a million of players with each game without a single penny spent in marketing, it also became clear, that the qualities people liked in our games and the players attracted to them were not served well with the free to play model.

Our main problem then became exposure – we needed a high amount of organic discovery (poaching players with ads had yielded too low a return to be worthwhile even if we could have afforded it) but had no way to create that. We also realized that, while quality and depth are attractive in bringing people in, the amount of focus we required (not session length, but actual concentration) made the games less suitable for mobile or tablet. Our assumptions about the market being ripe for a more core experience if made accessible enough and fitting within the shorter session times were similar to what motivated Super Evil Megacorp to do Vainglory and we suffered a similar fate (on a vastly more modest scale obviously). We were told by many people that they love the game, the quality was acknowledged, but when it came to the everyday playing behavior, people went for more convenient games that were a better fit to their use cases.

We began to look for ways to gain some free exposure on PC as mobile was clearly not the platform bringing in the money. Steam as well as Humble Store and similar platforms presented themselves – but a free to play game does not fare well on these, as we quickly realized. Pay to play games were more in line with the sensibilities of our most loyal customers anyway and for someone unable to spend marketing money, continued exposure can only be gained from sales and similar events as well as word of mouth (and the occasional PR). Also, our licenses resonated much more with a classic PC audience than with the younger mobile players, so that was an added bonus many games on Steam don’t have.

Bringing the games back from a design standpoint was fairly easy: Just get rid of the useless grind and time based mechanics (such as Energy) and bring back the economy to something that does not stop you from progressing at any pace you play. This alone increased our long term retention by almost 100% and what is more brought a large number of old players back, who had dropped the title due to the monetization mechanics (which admittedly had been a bit heavy handed at the request of the initial publisher, who was trying to establish a more aggressive “Asian MMO” monetization model).

Another issue with free to play games is new content – it is required to keep the game alive, yet it does not give you much added exposure (Maybe some people install their games based on the “New Updates” section of the app-store, but I doubt it brings in a huge numbers of new players). On a pay to play game new content can actually be released and gain you another exposure in store-fronts or be sold as DLC – so it feeds directly into revenue as opposed to you hoping it will improve your monetization or player base.

Another consideration is price point drops and finally bundling to make the most out of your life cycle. A free to play game that is not performing well has no life cycle – it was worth exactly zero to begin with and has no way to become more attractive from just a storefront standpoint nor will it achieve added organic discovery. This is why a title that does not quickly generate revenue in this day and age is quickly dropped by the larger publishers.

With Jagged Alliance we have brought a free to play game into a “try before you buy” style freemium that sold at €24.99€ and now – in the 3rd year of its existence – relaunched it at €9.99 as a completely pay to play game. And each time we made more monthly revenue than we had in an average month of free to play back when we had a publisher – and without any additional cost. Our revenue actually tripled even if discounting the first week of “launch window” attention a title used to get on Steam. We can now do sales actions to prolong that cycle down the line across various stores. Of course each cycle yields less revenue, but it keeps the game’s population alive on a small scale. If the game did not have a pay to play model, that would not be possible.

Lastly, it made us feel better about ourselves – suddenly our design discussions again centered on ideas and features, not optimization of small digit percentages from step A to B. It opened our horizon and as much as the initial focus on data driven design helped us think about games on a structural and gameflow level, it simply felt good to be able to think about features that were not part of some core monetization loop.

Now obviously the above is applicable to us and our particular brand of free to play games. Games that have a large amount of single player content, a deep enough gameplay and ideally speak to the core audience’s sensibility. It also is not a business model that I can recommend if your game is already successful in the freemium market. And clearly it is not a way to get rich quickly.

Interestingly, our revenue from in-game sales remained relatively stable relative to the player numbers for Jagged Alliance under transferring from free to play to “try before you buy” and we will now create DLCs for the pay to play version to make up for that revenue stream.

However we can sustain ourselves on the revenue we make, we have a much easier and risk free time calculating future revenues and we don’t have any cost outside operating and adding new content/features – which means we need to make much less revenue per player. We can promote our games through sales and active community work as opposed to an army of ad-optimizers. And we are liberated creatively.

As much as most of this is particular to our case, my expectation for the industry is, that f2p will kill the middle-strata of studios and publishers (the small guys always may find a niche or surprise success but by and large that is the same with pay to play), who cannot afford the rat race for customers and cannot carry over the success of their one or two old titles into a long term business. The same development we have seen in the browser space will hit mobile (or has already hit, but the sheer velocity of the market carries it onward, despite its legs being hacked off). Thanks to the limitations of the current business and design model in free to play (which for all its optimization has not seen much innovation outside of e-sports), that requires scale above all else, the pay to play model may be able to remain a niche as it is the only format allowing games that are different. It has certainly helped us to keep going and feel happier in our studio.